‘Even though there wasn’t any more shooting I was lonely for very different reasons.’

Posted by Siva Thangarajah on July 30, 2021The Bosnian War started in 1992, when Alma Aganovic was only 15 years old. She tells her story of how she was part of a medical evacuation to the UK after her brother was caught in the pathway of a bomb.

She also discusses what it is like to come to the UK as a teenager, and how she built a life here.

Alma and her children. Photo: Alma Aganovic.

I think one of the things that I felt as a teenager during the war was as though my life had stood still.

Before, I’d be going out every weekend and during the week I’d be going to school with my friends. And suddenly, my friends had gone.

The war started in April 1992. I was 15. My dad died in a car crash in the middle of the war in April 1993. It was caused by a car attempting to avoid the constant snipers all around.

During the war, there was an overwhelming feeling of boredom because I couldn’t do anything. There was no electricity, and there were no basic things like phones; all my neighbourhood friends had gone. I had nobody on my doorstep I could even have a chat with.

I look back on my teenage years with sadness because I just think that’s the time for living. And most of my teenage years I spent in the war, or being a refugee in the UK who didn’t speak English. So it just felt like from the age of 15 to about 19, I had no life.

In July 1993, my brother was outside playing in our front garden. There was a bomb blast, and he and many of his friends were injured. One of his friends was killed. I was upstairs studying and my mum was at work. I picked him up.

I didn’t really know what to do with him because the nearest working hospital was on the other side of the city. At the time, only vehicles were given to army forces. Luckily, there was a soldier who was coming back from work. He stopped his car, he loaded all the injured people in his car and drove them to hospital, including me and my brother.

I then went get my mum from work. I didn’t want her to come back home to us not being there and other people telling her what had happened. We then waited for the doctors to finish operating on him. He had suffered quite horrendous injuries on stomach and his jaw was shattered. What that meant basically was they had to wire his jaw shut to hold it in place, as his jaw bone wasn’t there anymore.

The doctors said, ‘Well that’s all we could do and we’ll eventually do a bone graft from his hip.’ But because his jaw was wired shut, he had to have liquidised food. As you can imagine that was quite difficult to do, because with the war we had no food anyway, so you had nothing to liquidise!

One day, the doctor said, ‘There is a medical evacuation of children and their families going to the UK tomorrow. ‘I’ve recommended that he should go because he needs further treatment. We can’t give him that here. Obviously he’s losing weight, and we really need him to gain weight.’

By the time we left for the UK, my brother weighed 24 kilos, and he was aged 11. I’ve now got a seven year old who weighs 28 kilos so that gives you an idea of how small he actually was.

We had less than 24 hours’ notice to pack. My mother packed a few things. Even though it was August, she heard we were going to England and it was cold there, so she packed jumpers and passports from former Yugoslavia which we no longer needed. To this day, she still says that the decision of what to take when you’re leaving your whole life behind is one of the most difficult decisions she’s ever had to make.

The Tape

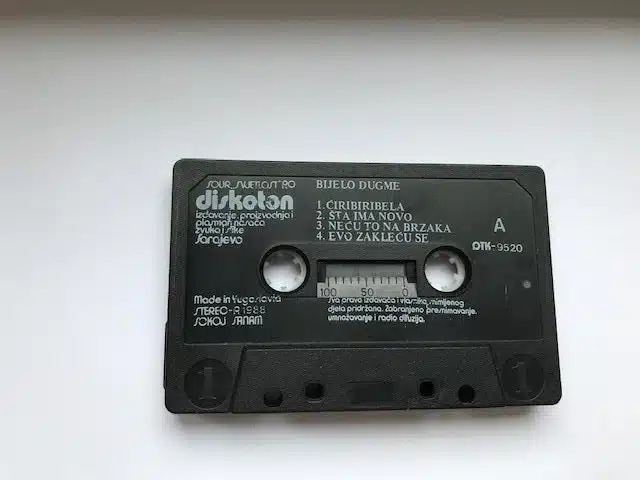

When we were leaving, my cousin came to say goodbye. He took us to the hospital because he was working for the Red Cross and had access to a car. He shoved this tape in my hand and said, ‘Take this with you.’

And I said, ‘Why are you giving me this tape?’

He said, ‘Trust me, when you get there, you will miss our music.’

And he was so right. Because as soon as I could get hold of a tape recorder, that was the only music that I had. This was in a time before internet; we’re talking early 90s, so there was no such thing as YouTube. You either had your music with you or you didn’t. And I did. And this tape was the only tape I listened to for years.

I also didn’t bring any of my belongings because my mom did all my packing. I don’t think at that age, you have anything that you are really attached to. After we moved to the UK, the tape was probably the only sanctuary I had when I was feeling homesick. It was just a local band called Bijelo Dugme. It stands for ‘White Button’ in English.

I was 17 when we came here as part of my brother‘s medical evacuation. We stayed in the children’s hospital in Birmingham, in family accommodation. That was difficult because we were sharing a room with another family. And we shared a bathroom and kitchen facilities with all the other parents. It wasn’t a proper cooking kitchen, just a microwave and kettle. We were eating canteen meals in the hospital. It wasn’t easy. It’s not like we had a house we could call home. We spent three months in the hospital; my brother stayed in hospital until November of that year, and then we got a flat.

Before he could have surgery, my brother had to put on weight, so the doctors were giving him loads of supplements. One of the big issues was the injuries on his stomach, which took a long time to heal because it was quite a deep injury and kept getting infected. His recovery wasn’t a straightforward process.

He had fractured his leg as well, a shrapnel took away part of a bone so one of his legs was shorter than the other; only by about a centimetre but still, he was limping and had to have extensive physiotherapy. He’s alright now, but it took a while.

Settling in the UK

When we came over to the UK, I started going to a language centre whilst we were staying at the hospital. I went there about 15 hours a week just learning English. So when my brother came home and we settled in, then I could draw a breath and think about myself for a change. It was at that point I decided to go to college.

Back home in Bosnia, I had finished three out of four years of high school, so I knew that roughly that was equivalent to A Levels.

My neighbour took me to a college that she picked at random. Incidentally, that’s where I work now. I carried on doing my English there, as ESOL, and then three A Levels on the side. I couldn’t really speak English properly, so I picked scientific A Levels as I thought they may be easier to understand. I did Statistics, Maths and Physics although I wouldn’t say I’m a scientist, really.

I made friends with the other students that were also doing English. They’d come over from Germany, France, places like that. Most of them were au pairs. If I spoke with broken English, it was okay, because they did too.

I didn’t feel like a normal teenager, I still didn’t go out, and do all the things teenagers do. Because I didn’t know this country. I didn’t know the city, and I didn’t know where to go. So from that perspective, my life still wasn’t normal.

The fact that I learnt English faster than my mum meant I still helped around the home, like going with my mum to medical appointments and things that most other teenagers wouldn’t do.

So even though there were no shootings here in Birmingham, I still I had to grow up very quickly.

Looking back at it, that’s what pushed me to do well for myself, be independent, and stand up on my own two feet.

Back then, part of me just wanted to say ‘Will you just let me chill?’ Because I never got a chance to just chill and be lazy and sleep.

I was very lonely for different reasons.

I miss home. I never really wanted to leave. We left because there was a need for medical treatment. When that ended, I started having a life here.

The war finished when I was halfway through university. When I finished my course, I got a job straight away, then a boyfriend, before I knew it, I’ve had a life here before I could stop to draw breath.

I thought, ‘Well, I can’t go home now.’ I’ve never really been an adult in Bosnia, I don’t know what that’s like. Once I’ve established myself as a citizen of this country, it became really difficult to think about going back.

I do think the UK is my home because this is where I have my family. My kids were born here. My partner’s Italian, but we met here, we have a house and jobs here. What is not helpful is that occasionally, you are reminded that weren’t really born here. If people ask me where I’m from, I say ‘Birmingham.’

People will say ‘Oh, you don’t sound like you’re from Birmingham.’

It’s those little micro moments. I’ll never really truly belong.

So I would say that from a very young age, this idea of identity, and questions like, ‘What am I? Who am I?’ All those sorts of questions became very difficult for me to deal with.

No one wants to leave their home, it’s just that people aren’t given a choice.

When we came here, we had a lot of good people around who helped us out. But there was also quite a lot of bad publicity, saying that the country should focus on itself as opposed to refugees.

I think that made me determined not to be a burden on the society; I wanted to prove that we weren’t going to come here and claim benefits.

When I was told that I couldn’t get a grant from university because I hadn’t been in the country of three years, I tried writing to charities and companies to get sponsorships and went to university anyway. I didn’t wait around for the system to help me. I didn’t take any time to take any time to feel sorry for myself. I just went ahead and found a pathway for myself.