‘I decided I couldn’t let my status dictate who I was’

Posted by IMIX on March 3, 2020Zino Onokaye-Akaka’s status affected a big part of her life in the UK. Now she doesn’t let it dictate who she is anymore and wants to share her story to change the conversation on migration.

It was Christmas Eve 2004, a very cold night. I was only nine at the time and I remember stepping out of the airport and thinking: ‘Ouch, I didn’t know cold weather was a thing!’

My parents made the decision to move to the UK because education here is better and a lot cheaper than in Nigeria where I was born. But when I realised that, since the system is different, I was going back two years at school, I cried so much. I thought it was going to be terrible being with younger people, which was really ridiculous because I was just smarter for a couple of years and then I joined everyone else.

At first, I was really upset because in a different country the thinking is different as well. I had a Nigerian accent and I was very conscious about that. So, from day one I was faking a British accent, which was actually American because of all the films I’d watched. Everyone kept asking me if I was American, even though for me my accent was so obviously British! There was a stigma on it. I just wanted to be myself without this extra weight of being different, of being from another country.

I remember that in primary school, after a summer break, it was typical to write a story about the holidays. I was terrified by that assignment because I didn’t know how to explain that I hadn’t gone anywhere on vacation. I felt like I should have done super exciting things, so I used to just make up a story of how I had travelled to another country, and it was super sunny and exciting. I wish I were able to talk about myself freely, the way I wanted to.

I’ve always known my status, I knew I wasn’t British. But it was only when I tried to do my university application that I realised how this affected who I am in this country. Because education is a fundamental right that everybody has, I thought it wouldn’t be an issue for me either. But I had to face the truth: my status didn’t allow me to go to university at that time. ‘You are a migrant’, I said to myself. In the UK, my status made who I was.

I didn’t want to talk with my teachers because of the stigma on immigrants, and I was scared about what they would say or do. I didn’t even know how to explain it to my friends because I knew they would just tell me to apply for citizenship, not knowing that it wasn’t that easy.

Eventually, I managed to get into St Mary’s University to study Psychology. I was really excited about it but, once again, that decision was based on my status. It’s a great university but I chose it just because of the price they would charge me and its accessibility so that I could use less transport. While other people based their decisions on the courses and the university’s prestige, I didn’t have that luxury which is a shame.

The first year was a real struggle to pay for my international fees. I was only able to pay half and the university told me not to come back until I had finished paying for them. I realised it was never going to work this way, so I decided to quit university. Except for my parents, I hadn’t told anyone about it, and when people asked me how things were going, I’d just said they were fine.

To terminate my studies, I had to fill in some documents and send them back to university. I scanned them in the church I was volunteering for back then, but I left some of my forms in the scanner by mistake. When I went back the next day to volunteer, my pastor called me out and asked me what those documents were about. Right there, I couldn’t lie to him and had to tell him that I couldn’t afford university. In my mind that was the end of everything, everybody else would have found out the truth.

What I didn’t know was that, behind the scenes, my pastor had talked to my university leader about this choice. He believed in my potential and couldn’t let me leave university. So, together with my whole church, my pastor made it possible for me to pay for the remaining two years. It was intense, I couldn’t believe so many people had contributed. I feel really grateful for the support of my community.

Throughout that time, whenever someone was talking about immigration, it was an uncomfortable topic for me. Normally I am very into conversations, but I felt like I didn’t want to give them a sign that I was different. I didn’t want to add that extra layer of my nationality, I just wanted to be like anybody else.

It took me a while before being able to deal with my being a migrant. I went to a charity meeting and at the end, everybody shared their experiences as migrants. Someone shared a story that was so powerful that I thought, ‘I can’t believe this person is going through this, it’s so unfair’. From that moment on, I decided I couldn’t let my status dictate who I was.

I wanted to help everyone else in my situation. I am now working at On Road Media. We try to improve media coverage of groups that have been misrepresented. I am really excited about my future in this organisation because it allows me to bring my psychology education and personal experience together.

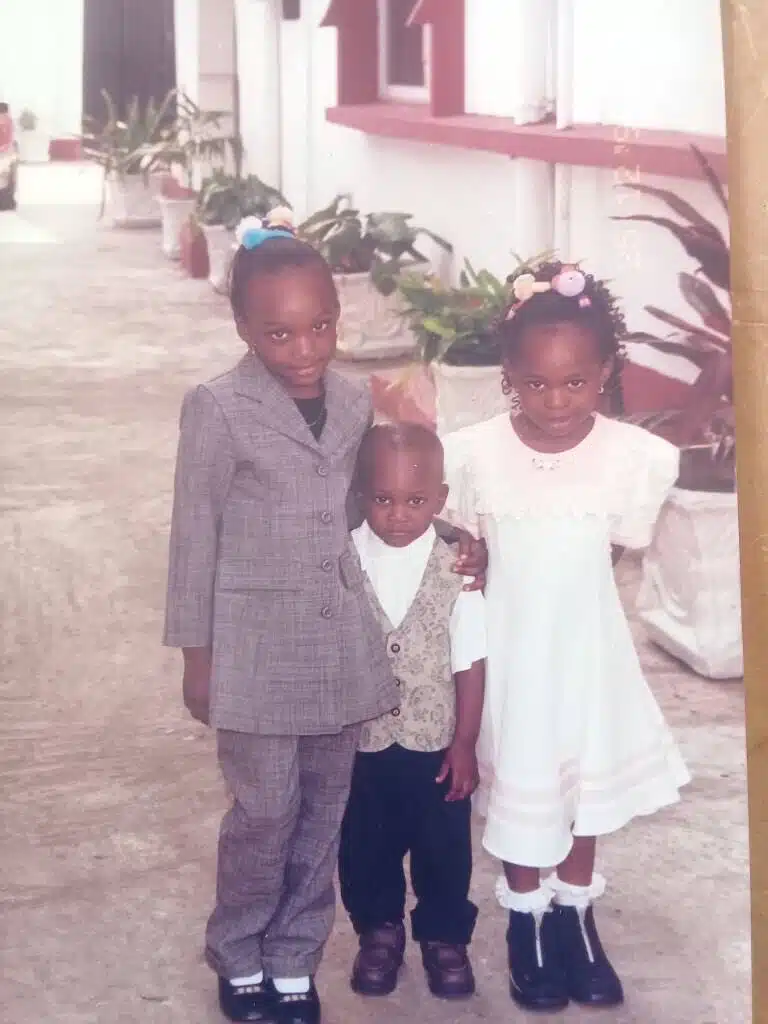

I don’t really have anything from Nigeria with me, but a thing that I had long-missed were pictures of when we were younger. Only a few years ago, when my dad got a lot of old photos from Nigeria, I finally saw myself a week old in a picture with my mum and my siblings. It was really amazing seeing me throughout the years, it reminded me of where I come from and the good times I had back there. These pictures are my laptop screensaver. When I look at them, I think that I love my family so much. We have been through a lot.

I only got my limited leave to remain status in 2016. It took so long. Having the support of my family helped me so much, we always had each other to rely on. After I met other people that were in my same situation, my family became much bigger and I had other people to talk to. My church and my faith have definitely helped a lot as well.

Through my personal journey, I came to terms with who I was. Being a migrant is a big deal but it doesn’t mean much to me anymore. It’s just a part of who I am, a section of me, but I am much more than that. Over the years, I have been able to talk more about it and, if by sharing my story people can see migrants in a more human way, I think that it changes the conversation overall.