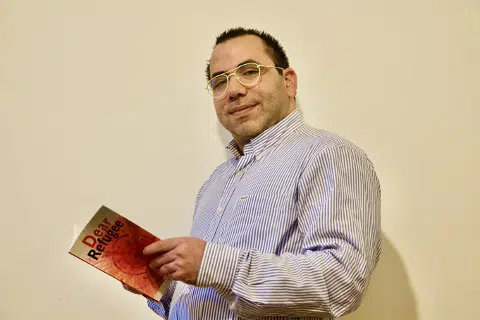

Writer and poet Amir Darwish: I’d tell my teenage self “Write away and speak your mind.”

Posted by Amir Darwish on May 5, 2023Amir Darwish is a British Syrian poet & writer of Kurdish origin who had to flee Syria to escape persecution after writing a poem for Kurdistan, the country he imagined that one day would be the Kurdish nation’s homeland. He had no choice but to make the perilous journey to the UK to seek safety in 2003. Now, two decades later, he reflects on the poem that drove him to flee his home.

It was all because of a poem.

I had just turned 17, and I’d been reading. My brother was a poet with a big library, but as I read through his books, I began to question why there wasn’t a Kurdistan. So, I wrote a poem.

It was just a naïve poem by someone discovering themselves as a writer. As a teenager, I just wanted to show my poem to someone, so I showed it to my brother’s friend, and he turned out to be an informant. There was a whole system of informants in Syria – that was how the Assad regime secured its power. They could be your brother-in-law, a neighbour, or the owner of the grocery shop where you bought your vegetables. The secret services didn’t try to hide it when they came to my house with machine guns. They just said: “You showed Ali the poem.”

My mum was terrified. The security services started to visit all the time. They asked me: “Where do you get your ideas? Where did the inspiration come from?” It was scary. Then they took me into prison and tortured me.

I was only released because my mum sold her jewellery to bribe them. That was the way things worked in Syria. I was told: “You have to leave the country in three days.” Mum managed to get me a passport and a plane ticket to Dubai.

Homeless, cold, and running out of time, I dreamed about England.

In the United Arab Emirates, I found a job and improved my English, but I couldn’t work freely as a writer and a poet. Breaking the rules in Dubai might be fine for some things, but not when it comes to criticising the politics, culture or society. Before I’d even penned another poem, a friend told me: “You’d better go somewhere else because if you write another poem here you will run out of places.”

At this time, before the war, it was still possible for a Syrian to get a European tourist visa. I flew to France, and then went to Belgium, hoping to stay with a family member, but it didn’t work out. It was January 2003. Homeless, cold, and running out of time, I dreamed about England. I spoke the language, and I knew the country as a famous defender of freedom of speech.

The night we crossed, it was snowing. My friend and I snuck into the depot where the shipping containers due to be transported across the Channel were waiting, and crept underneath the container. Our plan was to cling on while the containers were driven onto the ship, and remain in our hiding place until we reached Dover. In fact, the ship was going to Teesport, in the North East of England.

When I arrived in Teesport, I immediately claimed asylum. It was the start of another hard journey, and this one lasted years. I was refused, and then refused two times more. My documentation was mixed up with other claimants from Iraq. On top of that, back then, the Home Office decisionmakers claimed Syria was safe. I showed them the scars on my body from the torture, but they said: “You must have had somewhere in the country you can hide.”

What is a life if we don’t take a chance at it? I took a chance.

Eventually, I found myself living in the country without papers. With no identity confirming who I was, I was lost both metaphorically and literally. It was scary to walk down the street every day knowing the police could stop me, to wake up every day knowing I could be deported. If they send me back to Syria, I’ll spend the rest of my life in a prison. I’ll be tortured or maybe killed. My family won’t know what happened to me. These thoughts were in my head all the time.

Despite all this disappointment and fear, I was still a young man who wanted to discover the world. I used to go out sometimes with friends, and that’s how I met Emma. She was a local girl from Teeside. We met for coffee, and I cooked Syrian food for her. Eventually, we got married, and I could regularise my status through a spouse visa.

I was still passionate about writing, but I had to juggle it with other things. I got a job as an interpreter, but later I put myself through university, and started writing professionally. I write for magazines, and sometimes newspapers. It’s a struggle, but at least I’m doing something I love.

If I had the chance to speak to my teenage self again, as funny as it might sound, I’d tell them not to do anything different. I’d tell them: “Write away and speak your mind.” What is a life if we don’t take a chance at it? I took a chance. It might have been less costly if I hadn’t, but I never have regretted writing that poem.