Through a child’s eyes: What ethical reporting should look like on the border

Posted by Jenni Regan on July 8, 2025

Listening to Radio 4 last week, I was shocked—but not surprised—to hear the Home Secretary say she can’t wait for French police to wade into the water with knives to slash boats carrying people trying to reach the UK. There was no mention of what happens to the people on those boats. If they’re ‘lucky’, they’ll try again. But let’s be honest—state violence at the border means more injuries, more trauma, and more deaths. Deaths we, as UK taxpayers must take some responsibility for.

This week, the Calais-based charity Project Play released a report on the sharp rise in police violence against children—and a devastating increase in child deaths on the UK-France border. More children died there in 2024 than in the previous four years combined.

The report centres children’s voices. Miel (15) and Y (13), from Iraqi Kurdistan, shared:

“They bring out the knives and pepper spray then guns. I was like… I’m a child. Why are you doing this? We want to be safe and that’s it.”

The report doesn’t just document violence—it shows how policy decisions on both sides of the Channel are putting children at risk. At least 15 children died at the border last year. These aren’t accidents. They are political choices.

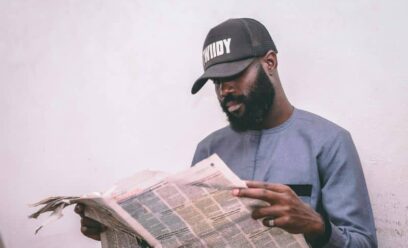

Much of the media continues to focus on numbers and dehumanising language—rarely showing the reality for children. This report helps change that. And this week, IMIX was in Calais to support Project Play with the release, providing media advice and safeguarding support. The media’s obsession with small boats has shifted from Dover’s cliffs to the beaches of northern France. Camera crews scramble to get the shot: desperate families clambering onto overcrowded boats, driven by UK policy and enabled by smugglers.

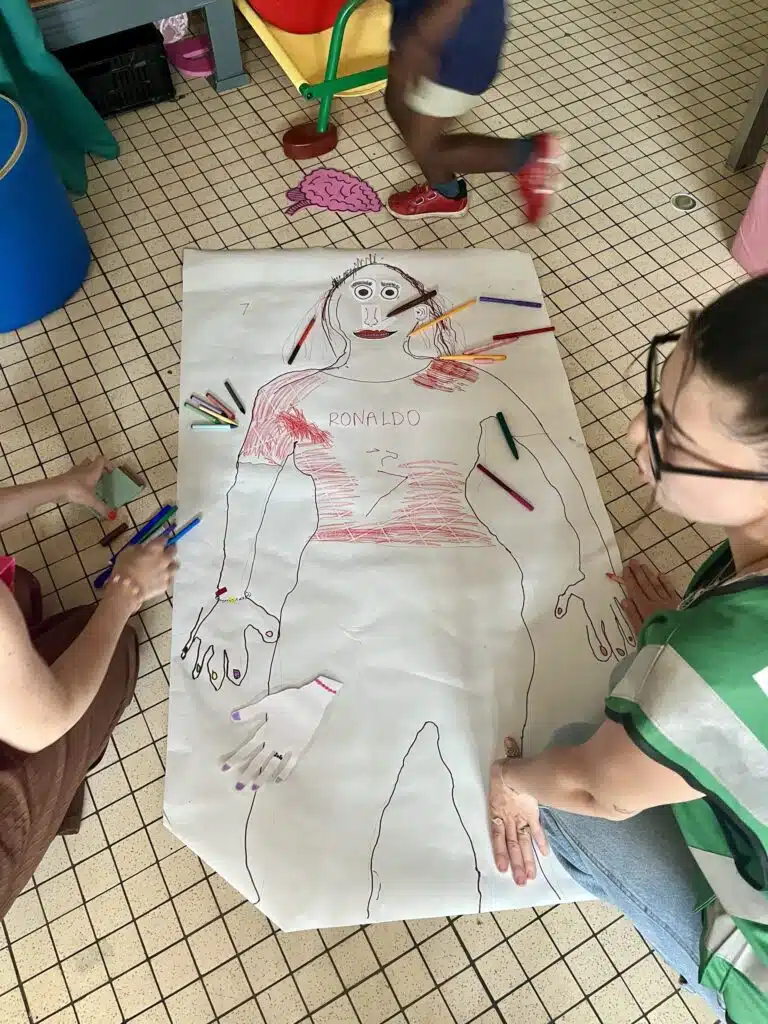

We spent time with some of those families—many who have reached the end of the line. The children we met had grown up displaced, often spending years in places like Germany or Sweden before their asylum claims were rejected and they were forced to move on. Again. At Project Play, we saw what safety looks like. Children running up to the team, knowing for a couple of hours they could just play. But there’s more going on. Structured activities, therapy, safeguarding. This is the only charity in the Calais area dedicated to working with children. Among the children we met was Mo, 10, obsessed with Ronaldo. A 12-year-old TikTok star from Iraq, surrounded by loom-band-making fans. And nine-year-old “Sally”, acting as an interpreter for her mum—who’d been tear-gassed just days before while trying to board a boat.

Channel 4, one of the few broadcasters to get it right, this time, interviewed Sally and her mum. But only after visiting three times, working with Project Play, building trust, and securing genuine consent. They took time to understand the situation and told the story with care.

Other journalists weren’t as patient. They wanted fast soundbites and quick edits. They soon realised traumatised children don’t make easy interviewees.

That doesn’t mean the stories aren’t there. Many have already been shared safely with the Project Play team. But most parents understandably refused to speak on camera, even anonymously. Many had experienced UK journalists ignoring safeguarding and twisting stories.

This mistrust deepened after a BBC report aired this week showing French police slashing a boat as people—including a clearly distressed child—looked on, their faces fully visible and no safeguarding measures in place. The footage appeared to ignore the BBC’s own editorial guidelines, which state that children’s welfare must be safeguarded, that vulnerable content must be handled with care, and that informed parental consent is generally required for children under 16. There was no clear public interest justification—just harm, risk and a dangerous lack of care. IMIX stepped in and secured the removal of the child’s image, but perhaps most concerning was that this happened without any acknowledgment that the BBC’s own standards had been breached.

The contrast with Channel 4 could not be clearer. They took time. They worked with experts on the ground. They gave the story context. They treated people with dignity.

That’s what ethical storytelling looks like. It’s not hard. But it does require time, respect, and a willingness to listen.