‘When people ask me about my nationality I say, I’m a Jewish, Egyptian-born, French-speaking British subject’

Posted by IMIX on January 20, 2021Doris Hugh and her family were expelled from Egypt in 1957 and resettled in England when she was 12 years old. She made the most of the opportunities she had in the UK, defying expectations by going to university and pursuing a career in education.

When people ask me about my nationality I say, I’m a Jewish, Egyptian-born, French-speaking British subject. I was 12 years old when I left Egypt. It was 1957 and the Suez Crisis led to the expulsion of British and French subjects. My family were Jewish, Sephardi Egyptians, but one of my ancestors had worked with the British in India and as a result my family had inherited some British passports, passed down the generations. Though we had nothing to do with Britain except for these passports, we were still expelled. We didn’t come to the UK like present day refugees, we were resettled in Britain and offered asylum there.

Doris Hugh in Egypt in 1952

I have fond memories of my childhood growing up in Cairo. Every summer there would be an exodus of the Cairo-Jewish population to the seaside. We would spend three months on holiday by the sea in Alexandria or Ras el-bar. Both my parents had siblings so I had many cousins. I went to school with them and was very close with most of them. Those summers felt almost primitive; our family would take over a whole row of straw huts by the sea and when our parents went to sleep after lunch, us kids would play outside. Family life in Egypt is what I’ve missed more than anything.

I remember the day the police turned up and knocked on the door. They stood there with the expulsion order telling us we had two weeks to get rid of everything in the house. My father’s brother and sister were also expelled and they left before us. My father managed to pull some strings to get us an extension, and we had a little extra time before we left on 3rd January. We had to sell everything we owned for pittance in a yard sale. Locals who knew we were being expelled showed up to buy our stuff for pennies; my parents were only allowed to take £5 each when we left.

The strongest memory I have of that time is from the morning we left. My mother was very upset. Our entire extended family came to the coach terminal to see us off at 6am. It was really very sad, I was in tears and so was my sister. We had no idea when we would see our cousins again. We didn’t know where we were going and we didn’t speak English. When we went through security they checked to make sure we weren’t smuggling anything valuable out of the country. I remember the security guard pulling the head off my doll to check there was nothing inside. The doll was never the same again after that.

Doris and family on holiday at Ras el-Bar in 1950

After the goodbyes the plane journey was actually quite exciting; as a 12 year old it was a new experience, I had never been on a plane before. Our first night was at a stop-over in Vienna, in a beautiful hotel furnished with dark oak. I remember the artist who cut out our silhouettes. I still have them somewhere. In Egypt we had slept with only a thin sheet but in Vienna we slept with a thick duvet. The next morning was fantastic, I opened the shutters to see snow for the first time. I’d only ever known snow as the cotton wool balls I’d stick on pictures. It was an amazing experience.

From Vienna we were taken to London where we spent a night in an old RAF base. Driving from there to the refugee camp in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, we passed lovely English houses. Even my mother looked interested then; we had lived in big blocks of flats in Cairo. The refugee camp was a disused military base near Nottingham, and was nothing like those houses. I still remember the smell of grease from the canteen that hit me as I got off the coach.

My mother burst into tears when we arrived at the camp. It was at the time of the Hungarian revolution so there were many Hungarian refugees there. One nice lady came and put her arms around my mother. They became friends in the camp. The food there was awful – bits of meat floating around in grease – but over the two months we stayed there I became quite happy with my new life. For my sister and me it was another novel experience. We made friends with the other refugee children and had great fun playing outside. I learned the hymn, ‘All things bright and beautiful’. After two months my father discovered some cousins of his living in Manchester and planned our move there. The day we left the camp I cried my eyes out; I had made a new life and once again it was being ruined.

When we arrived in Manchester I was lucky enough to have the equivalent of the 11+ from Egypt, and was accepted at a grammar school. My sister was only 9 years old and ended up at the local secondary school and had a totally different life from me. When I was first introduced to the class and they were told I was from Egypt, I got all sorts of questions: ‘Did you ride a camel, did you walk around barefoot in the sand, did you live in a tent?’ Cairo was actually a very metropolitan city, full of Europeans, and I was determined to show them I was just as good as them.

Within six months I had learned fluent English and was top of the class. One of the biggest changes to my life was my adoption of the European mentality, especially when it clashed with my parents. The idea of a ‘good Jewish girl’ going to university was anathema to them. I had to have the head mistress of the school call them in to persuade them, and eventually I was allowed to go, on the condition that I stayed living at home. I actually met my husband before university and we married after my graduation. I have had a long career in education as Head of Department and Head of Sixth Form, and now teach French part-time at a London school.

Doris graduating in July 1966

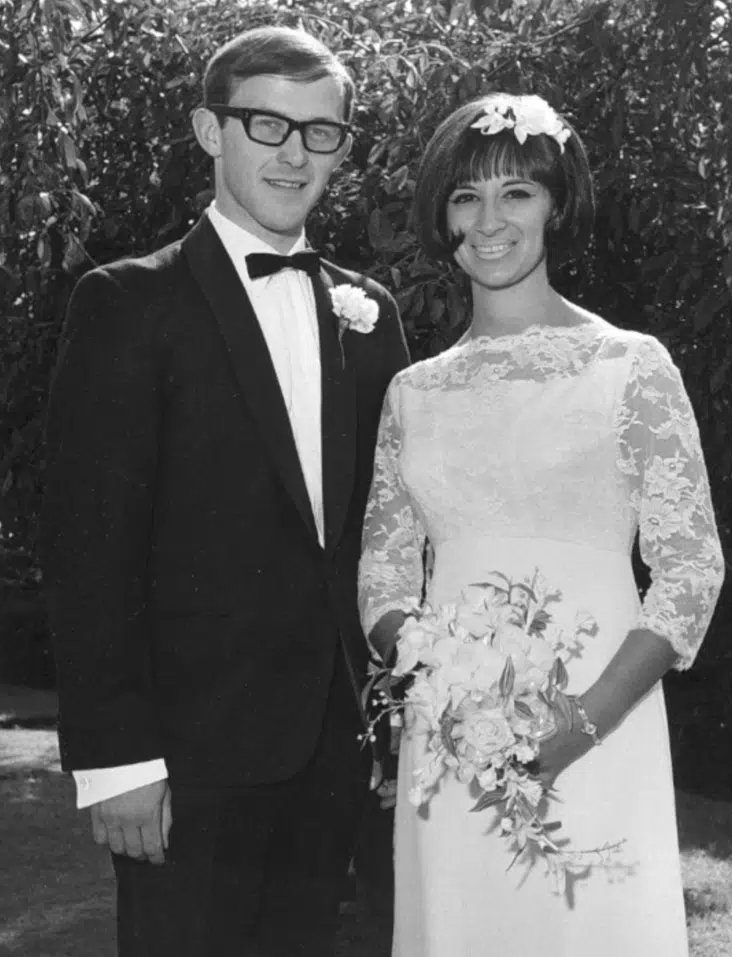

Wedding day, July 4th 1966

One way in which life in Cairo was different to the UK was that you didn’t have to prove your Jewishness. We were fairly secular and ate ham. It’s hard to explain to my children how much freer life was in Cairo. With all my cousins around, Jewish festivals were amazing. Even though my husband is not Jewish I knew I wanted to raise the children Jewish and keep a Jewish household. My daughter and daughter-in-law keep the Sephardi Middle Eastern tradition alive through their cooking.

After all these years I still don’t think of the UK as my home. In 1989 I returned to Cairo with my husband and visited my old house. I rang the doorbell and my Arabic came back to me. The caretaker was kind enough to let us in and offer us tea. We visited my old school and in every class the children stood up and recited a poem or sang a song for us in French. Cairo had changed so much. I used to live in a block of flats in Tahrir square, where the Arab Spring happened. I went to visit my cousin’s flat and it was all rubble. It was heartbreaking. Egypt isn’t my home anymore but it’s still where I grew up so happily.

Doris and her husband in 2019

To someone just arriving or embarking on a journey to the UK, I would say to them, you are lucky to be in a new country. Take every opportunity you can to develop yourself. That’s what I did. If I’d stayed in Egypt, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to go to university. I would say to them, look forward, don’t look back.